Part-1: Art in Turkiye

Art in Turkiye in the light of "Institutional Transformation of Arts in Turkey: Emergence of Private Art Museums" (Department of Sociology Ph.D. Thesis by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel, METU, 2014)

PART - 1: 1800-1980

Let’s delve into the Art in Turkiye in the light of "Institutional Transformation of Arts in Turkey: Emergence of Private Art Museums" (Department of Sociology Ph.D. Thesis by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel, METU, 2014)” and 2000s art scene in Istanbul with a focus on three trailblazing institutions: “Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum”, “Istanbul Museum of Modern Art (Istanbul Modern)”, and “Pera Museum”. This study traces the origins of private museums in Turkiye, arguing that these institutions emerged through a complex interplay of corporate interests, personal philanthropy, and the support of precursor philanthropic foundations.

For “ PART - 2 ” Click Here!

With the exclusive permission from the writer, excerpts taken from chapters 5, 6, and 7 of "Institutional Transformation of Arts in Turkey: Emergence of Private Art Museums" (Department of Sociology Ph.D. Thesis by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel, METU, 2014)”

INSTITUTIONAL AND LEGAL FRAMEWORK OF ARTS IN TURKEY

-Ottoman Legacy

The Ottoman Empire laid the foundation for modern culture and art institutions, which would serve as inspiration for future establishments. In the 15th century, the Imperial Treasury was established, housing gifts given to sultans, creations from the palace's workshops known as 'nakkaşhane,' and precious acquisitions from wars. It stands as one of the earliest imperial collections. Fatih Köşkü, also known as the Conqueror's Pavilion, was built during the reign of Fatih Sultan Mehmet II between 1562 and 1463. This historic pavilion served as the home for the collections of the Imperial Treasury. Documents from the 17th century, created by foreign guests granted access to the Treasury, indicate the presence of an inventory list. The collection was curated based on principles of uniqueness, high quality, and the personal tastes of the Sultans. During Sultan Abdülmecid's reign from 1839 to 1861, a portion of these valuables was first displayed in wooden cases, although the public was not yet allowed to view them. However, a significant part of the collection was eventually put on display when Topkapı Palace was transformed into a museum in 1924, thanks to Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's initiative.

In the late 19th century, as museums gained importance as symbols of nation-states in Europe, objects in museums became revered as witnesses of history. Under Sultan Abdülmecid's rule, the first Ottoman excavations began, leading to the display of excavated items in museum settings. This laid the foundation for the Imperial Museum in 1869, managed by French historian Edward Gould. The museum's first catalog in French was prepared in 1871. In 1872, the Imperial Museum was re-established with German Dr. Philip Anton Dethier as the manager, and the idea of opening it to the public emerged in 1873.

The Çinili Köşk (Tiled Kiosk) within the Topkapı Palace walls was restored, and in 1880, the museum reopened there. Osman Hamdi Bey took charge in 1881, ushering in a new era in Turkish museum development. He initiated significant archaeological excavations and introduced regulations for preserving the Ottoman Empire's archaeological heritage in 1884. In 1891, a new building for the Imperial Museum, designed by architect Alexander Vallaury, was constructed and is now part of the Istanbul Archaeology Museums (the Empire's first Fine Arts Academy). After his death in 1910, his brother Halil Edhem, transformed the museum into a modern institution, incorporating art from the academy and creating the State Painting and Sculpture Museum (now IRHM (İstanbul Resim ve Heykel Müzesi) (Istanbul Museum of Painting and Sculpture)) in 1937 under Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's leadership in the Republic of Turkey.

It's important to highlight that the Ottoman dynasty played a pivotal role in supporting the arts during the 19th century. They commissioned works from Western painters, patronized Western artists at the palace, and organized the first exhibition in Çırağan Palace in 1845. The Ottoman dynasty also supported Turkish artists by military funds, for their participation in the international exhibition in Vienna. In the early stages of Turkish painting, military-schooled artists who had received training in Europe played a significant role. They not only provided artworks but also played a crucial part in fueling interest in the arts. These artists were instrumental in organizing exhibitions and forming artists' associations.

Furthermore, during the 19th century in the Ottoman Empire, non-Muslim individual artists and families played pivotal roles in the art scene. For instance, the Guillemet atelier, established in 1874 in Istanbul's Beyoğlu district, held art exhibitions. The ABC Club, primarily composed of foreign artists, also contributed to the art scene. Additionally, Abdullah Fréres' photography studio was a notable presence.

Moreover, the Jewish-Ottoman Camondo Family, based in Istanbul, left a significant cultural and artistic legacy in the 19th century. They were known for initiating the construction of buildings that had a profound impact on Istanbul's cultural landscape. However, it's worth noting that their primary support for the arts was directed toward Europe.

Osman Hamdi Bey corresponded with Alexander Conze, the director of the German Museum of Antiquities when he was planning the Nemrut Mountain excavations. He reached out to his German contacts to seek funds for the project. Carl Humann, a German railroad engineer who had previous encounters with the excavation site in Bergama, advised him to gather funds from various sources. Subsequently, Osman Hamdi Bey collected funds from the Ottoman Bank, the Eastern Railway Company, and the Haydar Pasha Railway Company. This shows that even in the Ottoman Empire, banks were involved in supporting arts and culture, a tradition that continued into the Republican Era. The Imperial Museum's activities were widely publicized both within the Empire and internationally. For instance, the museum's acquisitions were featured in newspapers like Tercuman-ı Şark and Vatan, and they were also published in French, which helped bring recognition to the excavations on the European stage.

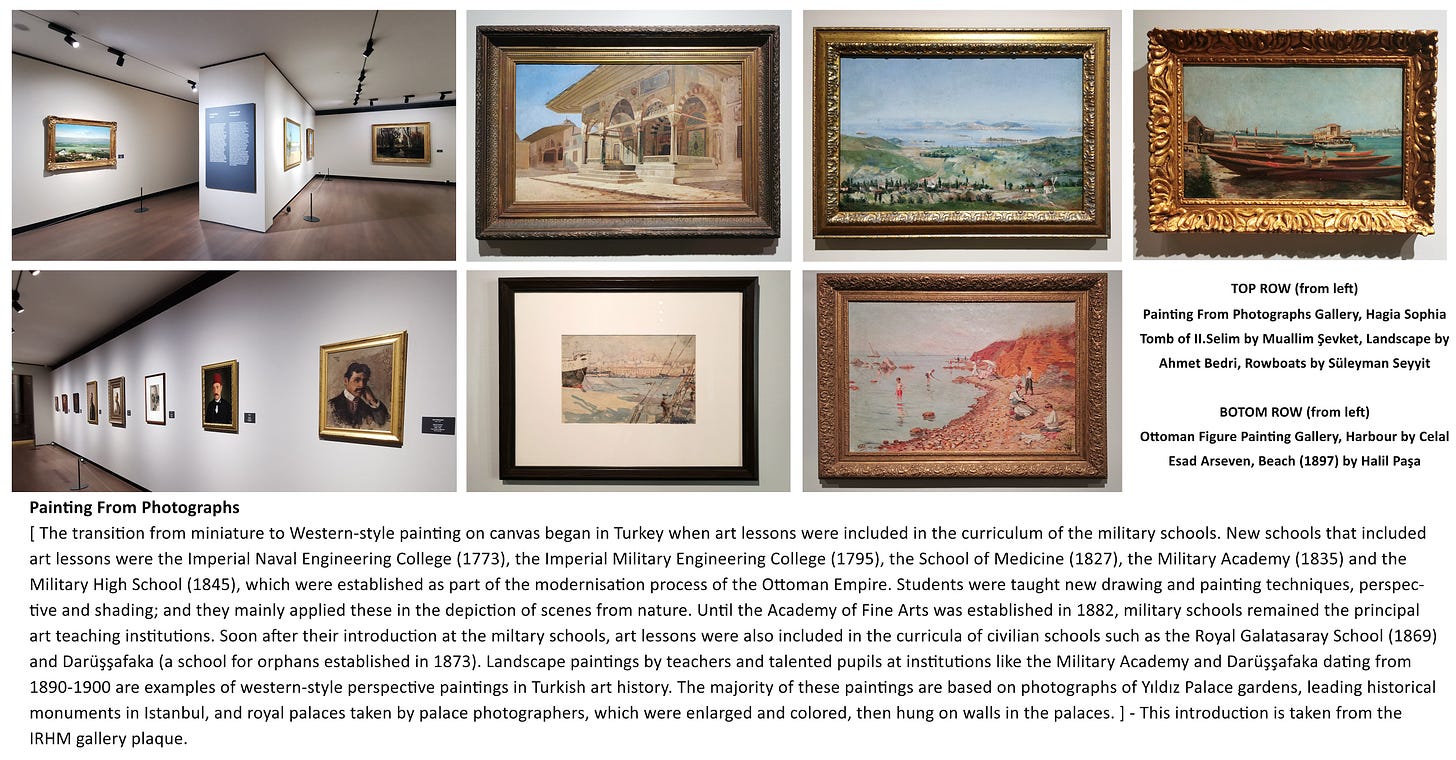

From the mid-19th century to the early 20th century, Turkish painting underwent significant development in the Western tradition. Key figures during this period are:

Ferik İbrahim Paşa (1815–1891)

Osman Nuri Paşa (c.1839–1906)

Osman Hamdi Bey (1842–1910)

Şeker Ahmet Paşa (1841–1907)

Halil Paşa (c.1857–1939)

Hoca Ali Riza (1864–1939)

The earliest painting lessons, primarily for technical purposes, were introduced at the Military School of Engineering (Mühendishane-i Berri-i Humayun) in 1793. Many artists who played pivotal roles in the 19th-century art scene had backgrounds in Ottoman military schools. Additionally, local Christian, "Levantine," and foreign artists residing in Istanbul and other parts of the Ottoman Empire made significant contributions to the art scene during this period. [Source: Wikipedia]

- Republican Turkiye

In early Republican Turkey, the state played a crucial role in shaping the field of arts. It facilitated the development of this field, building upon the Ottoman Empire's artistic legacy while aligning with new nation-state ideologies and the goal of creating a modern nation. Arts were seen as a means of education and enlightenment, integral to the nation's modernization.

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, the founder of the Turkish Republic, emphasized the importance of arts and culture in progress, stating,

"It should be confessed that there is no place on the road towards progress, for a nation which does not do painting, which does not make sculpture, which does not fulfill the requirements of science"

[Translated by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel. The original phrase in Turkish: Bir millet ki resim yapmaz, bir millet ki heykel yapmaz, bir millet ki fennin gerektirdiği şeyleri yapmaz; itiraf etmeli ki o milletin ilerleme yolunda yeri yoktur.]

“A nation deprived of art is a nation who has lost one of her veins”

[ Translated by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel. The original phrase in Turkish: Sanatsız kalan bir milletin damarlarından biri kopmuş demektir.]

The state actively supported the arts and artists, making it a key part of its policies. This included promoting national identity, expanding the arts within the country, participating in international exhibitions, and establishing new museums.

During the single-party rule of the Republican People's Party until 1950, the state acted as a significant patron of the arts. It supported artists' education and training in European art institutions, acquired artworks on behalf of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk as the country's President, commissioned paintings and sculptures, opened new museums, organized exhibitions, and developed the institutional and legal framework to promote Western forms of art and public interest in the arts. The state played a big role in shaping the art created. Sculpture and monuments became popular forms of art, with artists often focusing on themes related to the Turkish Revolution and Atatürk. Political leaders were crucial for art production and consumption. However, the absence of art galleries and dealers made it challenging for an art market to develop. Therefore, during this period, the state took on multiple roles in the art world, acting as the main supporter, audience, consumer, and critic of the arts.

State support for the arts was organized through a national framework. This included sending artists abroad for education, purchasing artworks from exhibitions, organizing official art exhibitions like Exhibitions of Reforms (İnkılap Sergileri, 1933-1936), launching Provincial Tours (Yurt Gezileri, 1938-1943) for artists, and providing educational and exhibition spaces through People's Houses (Halkevleri, 1932-1951). These efforts were coordinated at the Ministry of Education, which also served as the Ministry of Culture until 1935, forming the foundation of the emerging national infrastructure for the arts. While the state and ruling elites did encourage artists to emphasize themes related to "nationality" and the "achievements of the Turkish Revolution".

During this period, artists willingly created works that aligned with the state's missions because they were personally dedicated to the revolution. Artists organized themselves into associations and societies like;

* The Fine Arts Association

* Association of Independent Painters and Sculptors [ Hale Asaf (1905–1938), Muhittin Sebati (1901–1932), Ratip Aşir Acudoğlu (1898–1957), sculptor ]

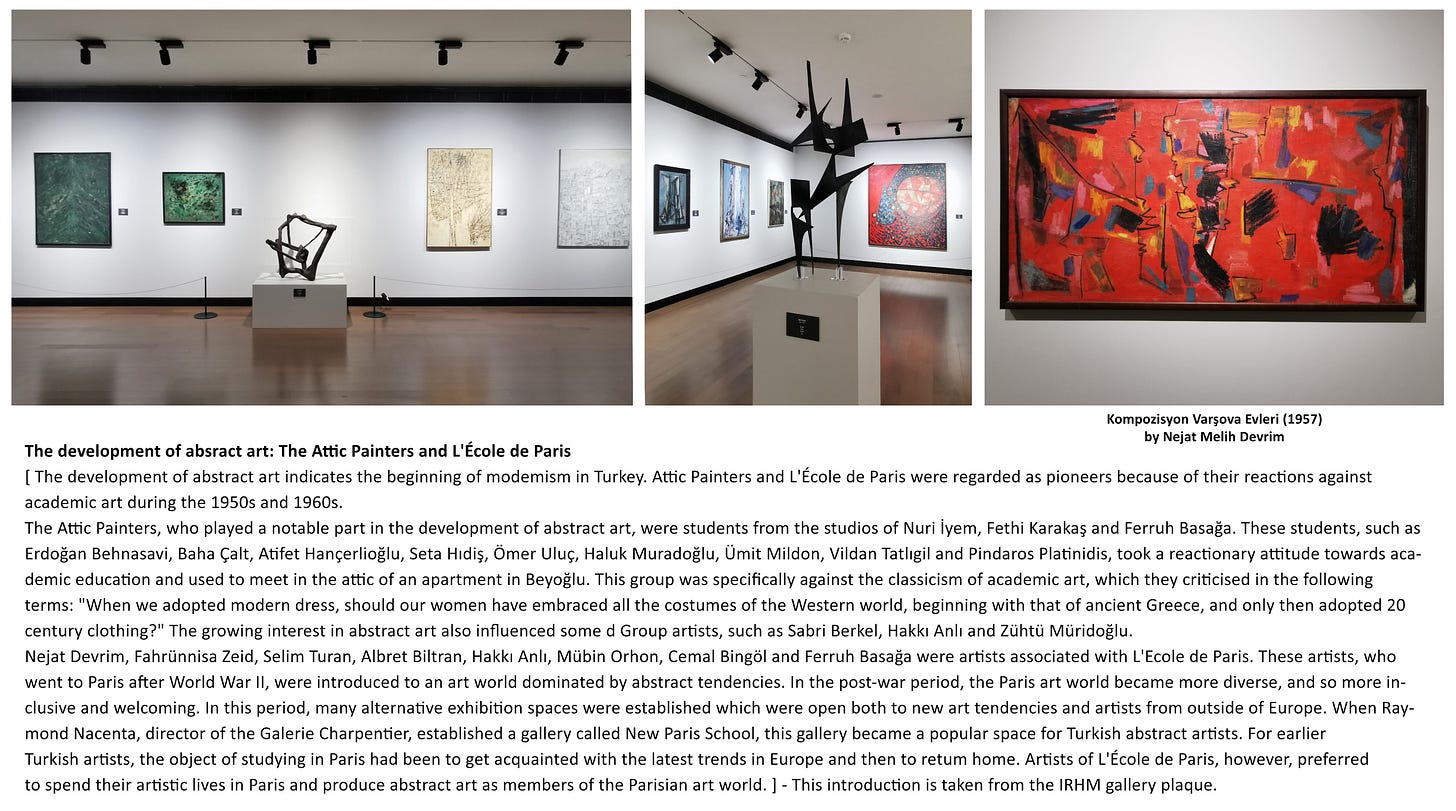

* Group D [ Abidin Dino (1913–1993), Cemal Tollu (1899–1968), Bedri Rahmi Eyuboğlu (1911–1975), Fikret Mualla, Adnan Coker (born 1927), Fahrunissa Zeid (1901–1991), Burhan Doğançay (1929–2013), Turan Erol (1927-2023) ]

* Newcomers Group (Harbour Painters) [ Avni Arbaş (1919–2003), Abidin Elderoğlu, Ercument Kalmik, Neş’e Erdok, Eren Eyüboğlu, Sabri Berkel ]

* Siyah Qalam Group (1960s) [ İhsan Cemal Karaburçak, Cemal Bingöl, İsmail Altınok, Ayşe Sılay, Selma Arel, Lütfü Günay, Asuman Kılıç, Solmaz Tugaç ]

* 1968 Generation [ Alaettin Aksoy, Gürkan Coşkun, Mehmet Güleryüz, Neş’e Erdok, Nevhiz Metin, Ömer Kaleşi, Utku Varlık, Reşat Atalık, Özdemir Altan, Cihat Burak, Nedim Günsür, Neşet Günal ]

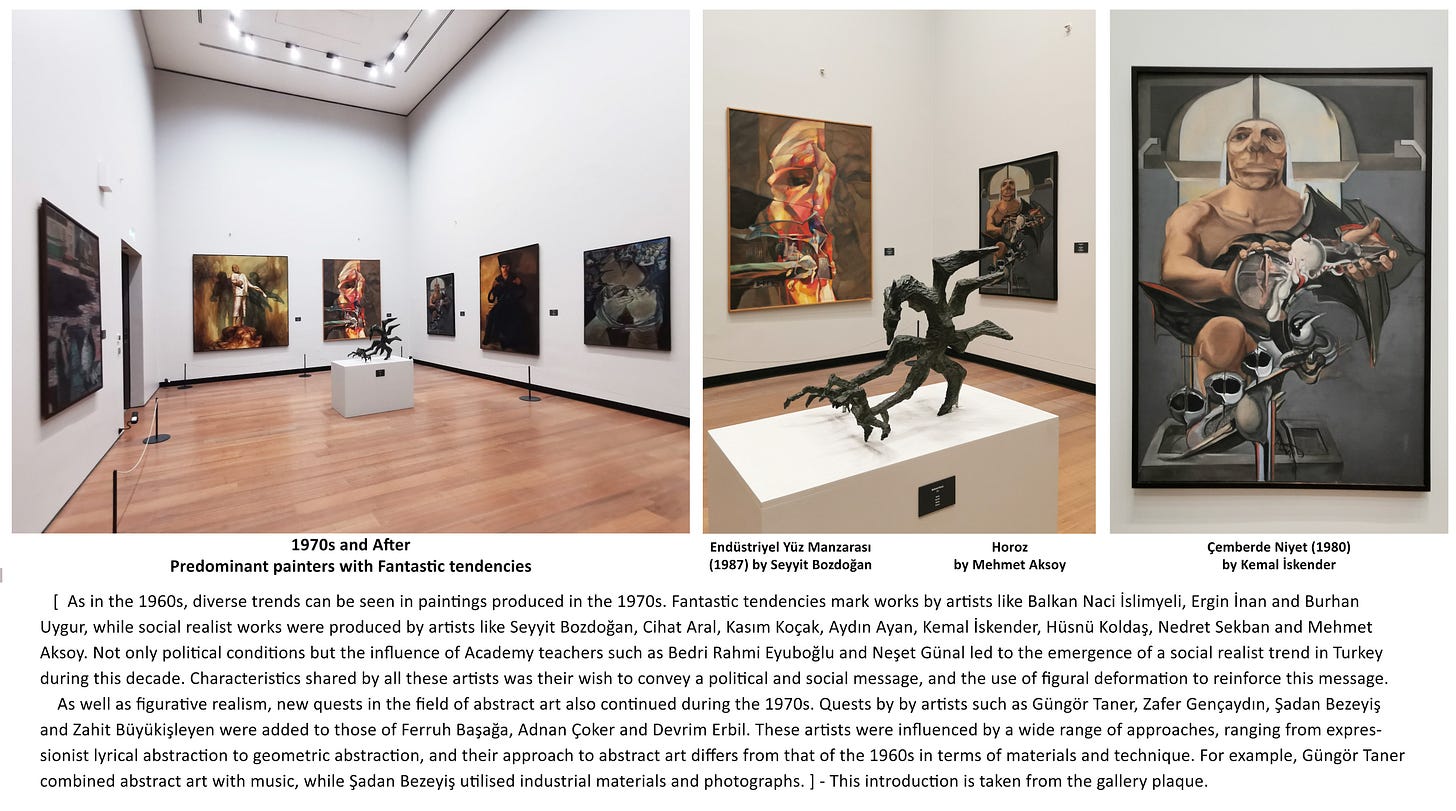

* Social Realists [ Seyyit Bozdoğan, Cihat Aral, Kasım Koçak, Aydın Ayan, Kemal İskender, Hüsnü Koldaş, Nedret Sekban, Turgut Atalay, Mehmet Aksoy, Nevzat Akkoral ]

* 1970s and After (with fantastic tendencies) [ Balkan Naci İslimyeli, Ergin İnani Burhan Uygur, Mevlüt Akyıldız, Hüsnü Koldaş, Kemal İskender, Seyyit Bozdoğan, Zekai Ormancı, Temür Koran ]

These groups needed state-sponsored exhibitions in addition to their efforts because there were no intermediaries like galleries or art dealers.

Ankara (capital of Türkiye) emerged as the cultural and artistic heart of the new Republic, with exhibition spaces like Ankara Sergi Evi (Ankara Exhibition House), People's Houses, the Fine Arts Academy, and Galatasaray Lycee in Istanbul played key roles. The Ministry of Education took center stage as the main institution purchasing artworks on behalf of the state. Minister Hasan Ali Yücel, particularly during the period between 1940 and 1950, wielded a significant role in shaping the state's cultural policies and support for the arts.

In 1937, a landmark moment unfolded in Turkish art with the organization of the "50 Years of Turkish Painting and Sculpture Exhibition." This event coincided with the opening of the Istanbul Painting and Sculpture Museum in the Heir's Quarters of the Dolmabahçe Palace. The museum's core collection included original paintings and reproductions collected by Osman Hamdi Bey and Halil Edhem, artworks owned by the state, and transformed palace museums and pieces displayed. However, it's crucial to note that Turkiye lacked a modern art museum, which was a significant concern in the field. This was mainly due to the museum's historical reliance on donations from artists and official state institutions. In 1936, the "Exhibition of Modern Turkish Painting" traveled to Athens, Bucharest, Moscow, Leningrad, and Belgrade. Exhibitions abroad became more frequent in the post-World War II era, demonstrating the state's active involvement in promoting Turkish art internationally.

In the early years of the Republic, while the artistic production and consumption primarily revolved around Ankara, it also continued in Istanbul. This transition coincided with a reduction in state support for the arts and the subsequent emergence of an art market and cultural industries in Istanbul. Ankara, as the capital city, was officially designated as the new center of culture and arts for the Republic. This decision was made by the Council of Ministers in 1926, and it stated that exhibitions held in Ankara would be considered official. It also introduced awards for artists and initiated the purchase of paintings. Several key events contributed to establishing Ankara as a cultural hub. These included the opening of the Painting Department at the Gazi Educational Institution in 1931, the launch of the "Exhibition of the Paintings of the Revolution" in Ankara People's House in 1933 (which continued until 1937), and the annual State Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture, first held on 1939, in Ankara. These activities played a vital role in achieving the goal of positioning Ankara as the epicenter of the arts.

However, as the multi-party period began in 1946, the state's role in the arts started to diminish, paving the way for private initiatives to take center stage. This period had distinct characteristics:

Introduction of a multi-party political system in 1946 and the opposition party coming to power after the May 1950 elections.

Economic challenges during the aftermath of World War II, including high inflation and new taxes, eroded support for the ruling Republican People's Party (CHP). The Democrat Party (DP) took power as the sole opposition party.

DP's policies appealed to a broader range of social groups and emphasized traditional values, populism, and the instrumental use of Islam.

Initially, the Turkish economy experienced growth with the support of U.S. aid. However, this growth gave way to economic stagnation and soaring inflation in the mid-1950s, leading to authoritarian rule and increased use of Islamic symbols for propaganda.

A new perspective on Turkish history emerged, with the DP looking favorably upon the Ottoman era.

During the DP's governance, People's Houses (Halkevleri, 1932-1951) were closed in 1951, leading to a decline in the importance of culture and arts at the policy level. This period witnessed:

Increased individual efforts by artists to create and distribute their works.

The growing significance of social groups with disposable income, becoming potential art consumers.

A rise in the number of exhibitions organized by artists and a decrease in official exhibitions.

Greater participation of Turkish artists in international events such as the Venice Biennial and Sao Paolo Biennial.

Istanbul's ascension as a hub for new artistic initiatives reduced the importance of Ankara.

The absence of art dealers prompts artists to find creative ways to sell their work, including permanent exhibitions, installment payment options, and discounts.

The emergence of architectural sites like Anıtkabir, the Grand National Assembly of Turkey, Etibank Headquarters, hotels, and the Izmir Fair as opportunities for artists to earn a living.

An examination of the cultural policies during this period reveals several initiatives. These included efforts to strengthen cultural relations with the United States of America, France, and Britain, the passage of bills to protect works of art, increased funding for public museums to support exhibitions and exhibition complexes, and agreements to boost revenue sources for museums. However, it's important to note that as attention to the arts vanished and economically liberal policies were introduced, there was a noticeable increase in individual exhibitions and the establishment of art galleries. This development can be seen as filling the void left by the state's reduced role as the primary supporter and provider of the arts. A significant development in the 1950s was the emergence of private art galleries in Istanbul and Ankara. These galleries, including Helikon Derneği Galerisi, Milar Mobilya ve Dekoratif Sanatlar Galerisi, and Sanatseverler Derneği Galerisi in Ankara, aimed to fill the gap left by the closure of People's Houses. These galleries catered to the affluent and cultured individuals of the time. While they served as vibrant hubs for intellectual circles, both in Istanbul and Ankara, they indicated the state's diminishing role in funding the arts during this period.

The 1961 military coup can be seen as a response from the official elites, both military and civilian, who were concerned about the decline in their power, prestige, and societal status during the era of the Democrat Party's rule. It was also an attempt by the military bureaucratic elite to regain a central role in the country's politics and address perceived threats to Islam and Kemalist principles. The coup led to the enactment of a new constitution by the military rulers, which adopted a more liberal approach to secularism, religion, and individual and social rights. It introduced institutions like the independent constitutional court and the National Security Council, providing the military with a special platform to intervene in the country's politics. The constitution aimed to prevent elected governments from abusing their authority through authoritarian rule and replaced the majoritarian electoral system with a proportional one. Subsequent elections in 1965 and 1969 resulted in the victory of the Justice Party but also brought about political turmoil due to increased polarization between the right and left. Furthermore, it's important to note significant economic advancements that paved the way for the private sector to become a prominent participant in various aspects of society. After the 1961 Constitution, there was a period of political instability with short-lived coalition governments. Notably, events organized by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (İKSV) sparked controversy. Leftist groups criticized the festival for being elitist due to high ticket prices, while conservative right-wing groups criticized it for not representing Turkish culture and for promoting foreign cultures. During this time, out of fifteen different governments, five had a Ministry of Culture, but cultural policies remained mostly in the realm of words. This period was marked by insufficient funding, a lack of permanent staff, and an absence of coherent cultural policies. The state, which had previously been a major supporter of the arts, saw a diminished role in providing and supporting the arts.

While the State Arts and Sculpture Exhibition was held in 1973 to commemorate the Republic's 50th anniversary, the state began to focus on international events for promotional purposes. The political atmosphere led to censorship of artworks from ideologically opposing groups, leading to incidents such as attacks on artworks at the Antalya Painting and Sculpture Exhibition in 1976 and the removal of sculptures in Istanbul's 20 Sculpture Project. Conservative groups also criticized the State Fine Arts Academy for not reflecting the national culture.

Changes in the economy and the accumulation of wealth by certain individuals, families, and philanthropic foundations, including the Vehbi Koç, Sakıp Sabancı, and Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı and their families, paved the way for the development of an independent art market. Several economic and political factors contributed to the emergence of this art market. The emergence of philanthropic foundations played a significant role in fostering the idea of establishing museums and promoting support for the arts through a collective framework provided by these foundations.

Turkey experienced coalition governments until the late 1970s, a period marked by economic difficulties exacerbated by events like the Cyprus intervention in 1974 and the 1973-1974 oil crisis. This era also saw the beginnings of identity politics, societal conflicts, violence, and assassinations. Notably, Demirel, the leader of the Justice Party Government, initiated a significant economic reorientation, appointing Turgut Özal as the head of the State Planning Organization (SPO) to launch a new economic policy aimed at economic liberalization. Regarding arts funding and the emergence of an art market in Turkey during this period, several noteworthy developments occurred. There was a notable increase in the number of private galleries and auctions. Most importantly, the private sector began to play a significant role as a source of demand for the arts. Additionally, the media played a crucial role in disseminating information related to the arts. Various periodicals like Milliyet Sanat, Yeni İnsan, Ankara Sanat, Varlık, Hisar, Yeditepe, and Arkitekt contributed to spreading news about art and relevant topics, including discussions on the "value of the work of art."

The role of banks in supporting the arts has a long history in Turkey, dating back to the Ottoman Empire. During that time, the Ottoman Bank provided support for excavations in Nemrut Mountain. However, it was during the early Republican period that bank support for the arts became more significant. In the late 1960s, banks began to play a more explicit role in shaping the demand for art. Alongside building their art collections, banks such as İş Bank, Yapı Kredi Bank, and Akbank established exhibition spaces within their corporate buildings, with the Galatasaray and Beyoğlu districts in Istanbul emerging as centers for art exhibitions and initiatives.

Moreover, other sectors of the economy also recognized the advantages of supporting the arts for enhancing their corporate image and reputation. In the mid-1970s, the exhibition spaces within banks transformed into galleries. Simultaneously, owners of capital and high-level executives started collecting artworks in the late 1960s and showcased their collections through exhibitions in the 1970s. Despite various challenges, processes of urbanization and capitalization resulted in the accumulation of wealth among specific groups. There was a noticeable shift in the individuals and groups who possessed artworks, with ownership moving from intellectuals to individuals in the private sector. This shift reflected the growing social differentiation in Turkish society and marked the emergence of the concept of artworks as investments and symbols of high social status.

Türkiye İş Bankası (İş Bank) which was founded in 1924 and has started to establish its collection, the interest in buying works of art led by Bank‘s Vice General Manager Saim Aybar, in an environment vitalized with the flourishing of the State Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture and from 1940 and onwards bank appeared as the consumer of the works of art. Awards for the arts have been established by the banks which have had an important impact in the sphere of artistic production.

Ziraat Bankası (Ziraat Bank) commissioned works from Namık İsmail, and İbrahim Çallı and bought works from the State Exhibition of Painting and Sculpture.

Yapı ve Kredi Bankası (Yapı Kredi Bank) which was founded in 1944, right from the beginning encountered the sphere of arts with the enthusiasm of its founder Kazım Taşkent. Acquisitions influenced by the art and culture consultancy of art connoisseur Vedat Nedim Tör. Yapı Kredi Bank organized an award exhibition in 1954, marking one of the earliest examples of instrumentalizing an art event for a business purpose. This event had a significant impact on questioning the Academy, the quality of artwork, and the concept of national art. Aliye Berger, an amateur artist, won the award with her work titled "Sun," challenging the prevailing trend of artists producing "copies" of Western paintings and dedicating themselves to cubism. This competition led to criticisms and a shift toward abstract painting in Turkey's art scene. In the 1960s a space was allocated for exhibitions in Galatasaray.

Türkiye Cumhuriyeti Merkez Bankası (Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey) was added to the list in the 1940s.

Akbank is another important example considering Akbank Art Center in Beyoğlu since 1993 and organized two major events: Akbank Jazz Festival since 1991 and Akbank Short Film Festival since 2004, the main sponsor of IKSV organized Film Festival.

Garanti Bank is a crucial example of the establishment of SALT (2011)

DYO organized an exhibition in 1967 with a scope of Aegean region

Mobil Oil Company introduced an art award in 1970

Vakko opened ―Vakko Art Gallery on İstiklal Street in 1962

Sadberk Hanım Museum (Vehbi Koç Foundation)

Sabancı Museum

Pera Museum

İstanbul Museum of Modern Art

The aspiration of establishing a Museum flourished within the framework of İKSV. The history of the museum is closely associated with the history of İstanbul Biennial organized by İKSV.İstanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (İKSV) is a non-profit and non-governmental organization founded in 1973 by seventeen businessmen and art enthusiasts who gathered under the ―leadership of Dr. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı. İKSV is located in İstanbul and concentrated on the city, rather than acting nationwide, and has organized international festivals which are mostly based on bringing international artists and performing artworks.

The official aim appeared in the founding waqf deed states that the aim of the foundation was: ―to appraise our country‘s potential for tourism; and organize international culture and art festivals in various regions of the country with the purpose of introducing all aspects of our national culture to the public‖ (Official Gazette of Turkish Republic, 29 June 1973).

ISTANBUL MUSIC FESTIVALISTANBUL FILM FESTIVAL

ISTANBUL BIENNIAL

ISTANBUL THEATRE FESTIVAL

ISTANBUL JAZZ FESTIVAL

PAVILION OF TURKEY AT BIENNALE ARTE AND ARCHITETTURA

CİTÉ INTERNATIONALE DES ARTS RESIDENCY PROGRAMME, TURKEY İKSV STUDIO

CultureCIVIC

SALON İKSV

CULTURAL POLICY STUDIES

LEYLA GENCER VOICE COMPETITION

AYDIN GÜN ENCOURAGEMENT AWARD

TALAT SAİT HALMAN TRANSLATION AWARD

GÜLRİZ SURURİ - ENGİN CEZZAR THEATRE ENCOURAGEMENT AWARD

Borusan is a large industrial conglomerate founded in 1972 by incorporating various Borusan companies and has an institution called Borusan Sanat (Borusan Art) which hosts Borusan Istanbul Philarmonic Orchestra, Borusan Quartet, Borusan Classic, Borusan Contemporary (Office museum of contemporary arts), The Borusan Music House, music awards and publications.

MORE ON THE SUBJECT:

* AN EXISTENCE STORY: ISTANBUL IN TURKISH PAINTING - TURKISH PAINTING IN ISTANBUL by Elif Dastarlı (source)

RELATED POSTS:

* Art vs. Censorship: Navigating the Boundaries of Expression

Will Attempts to Control Artistic Expression for Authority Succeed?

* The Enduring Love Affair: Exploring the Allure of Art

Why do we love the Arts? Will it cure us?

* The Artistic Alchemy: Unraveling the Correlation Between Persona, Psychology, and Art Styles

Is an artist's style determined by their persona? Can anyone become an artist, or is it an innate trait?