Part-2: Art in Turkiye

Art in Turkiye in the light of "Institutional Transformation of Arts in Turkey: Emergence of Private Art Museums" (Department of Sociology Ph.D. Thesis by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel, METU, 2014)

PART - 2: 1980 AND ONWARDS, Philanthropic organizations

Let’s delve into the Art in Turkiye in the light of "Institutional Transformation of Arts in Turkey: Emergence of Private Art Museums" (Department of Sociology Ph.D. Thesis by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel, METU, 2014)” and 2000s art scene in Istanbul with a focus on three trailblazing institutions: “Sabancı University Sakıp Sabancı Museum”, “Istanbul Museum of Modern Art (Istanbul Modern)”, and “Pera Museum”. This study traces the origins of private museums in Turkiye, arguing that these institutions emerged through a complex interplay of corporate interests, personal philanthropy, and the support of precursor philanthropic foundations.

For “ PART - 1 ” Click Here!

For “ PART - 3 ” Click Here!

With the exclusive permission from the writer, excerpts taken from chapters 5, 6, and 7 of "Institutional Transformation of Arts in Turkey: Emergence of Private Art Museums" (Department of Sociology Ph.D. Thesis by Gözde Çerçioğlu Yücel, METU, 2014)”

1980 AND ONWARDS: THE CONTEXT FOR THE EMERGENCE OF PRIVATE MUSEUMS

Economic and Social Context

Framed by the economic liberalization in the 1980s and onwards, the social implications of neoliberalism and the relevance of post-1980s social and economic context with the rise of private investments in arts are to be discussed.

In 1980 Turkey witnessed a military coup on September 12 and this date marked an important rupture in the political, social, and economic history of Turkey. In the aftermath of the 1980 military intervention, the Motherland Party (ANAP) governed Turkey with the leadership of Turgut Özal between December 13, 1983-October 31, 1989. In 1989, Özal was elected in the third round of the Presidential election on 31 October 1989 and became the 8th President of the Turkish Republic. Motherland Party was founded by the active engagement of Turgut Özal in its establishment in the 1982-1983 period and later symbolized by his name. The party claimed him to be different than other political parties because of its emphasis on representing the “main pillar of the society” (Ersin Kalaycıoğlu 2002) and surpassing the elite vs non-elite divide in the Turkish society (Ziya Öniş 2004). Özal‘s desire for a “modern society held together by conservative values” (Kalaycıoğlu 2002) characterized the image of the Motherland Party which hosted contradictory ideological strands of conservatism, nationalism, economic liberalism, and social democracy. Özal is referred to as the “pious agent of liberal transformation” by Acar (2002) and later by Öniş (2004) as a strong representative of neoliberal populism.

Turgut Özal and Motherland Party (ANAP) under his leadership considered crucial for restructuring the economy in the neoliberal direction and for transforming the economic and social history of Turkey (Metin Heper 1989 and 1990; Kalaycıoğlu 2002; Sabri Sayarı 1996). Özal played a significant role “in the liberalization of the economy” and “in the shift from import substitution to export orientation in Turkey” which are considered important steps “toward a strong state vis-à-vis the economy” (Heper and Keyman 1998).

The impact of Özal on Turkey‘s economic liberalization history is traced back to his appointment by Demirel to plan and implement an economic reform program when he was the head of the State Planning Organization (SPO) in 1979. This program was aimed at planning and adopting economic and financial measures to integrate the country with the world economy. This reform program was instigated on 24 January 1980 and is often referred to as the “24 of January Decisions”. [The 24th January 1980 Decisions were announced to curb inflation, to fill in the foreign financing gap, and to attain a more outward-oriented and market-based economic system.]

As Boratav (2004) summarizes the particularities of the program were: devaluation, abolishment of raises in the state-owned enterprises, abolishment of price regulation. According to Boratav, the program took measures that were even beyond the requests of the International Money Fund (IMF). Moreover, the program had major goals of establishing domestic and foreign trade and strengthening national capital towards labor in concordance with the promotion of the World Bank and international capital. Thus, it was not only a stability program but rather a structural adjustment one; it contained both the elements of the standard stability policy package imposed on many underdeveloped countries by the IMF in the 1970s and the structural adjustment program developed by the World Bank. As Boratav argues the program was away from consistent and systematic implementation before the military intervention.

an association between the competitive working conditions of commercial banks and their engagement in ‘social responsibility’ projects. Banks started to compete in the non-economic areas under the framework of social responsibility projects. Culture and arts are determined as an area under this framework. Sponsorships, support of banks in cultural events and art exhibitions, and their establishment of cultural and artistic platforms during the 1990s can be evaluated in this respect.

Cizre & Yeldan (2005) studied Turkey‘s encounters with neoliberalism. Cizre and Yeldan (2005) emphasize the rise of the “hegemony of the neo-liberal orthodoxy”, the rhetoric of “there is no alternative” and the aims of neoliberalism. Neoliberalism aims to build the conditions suitable for the profitability of the capital, and it has a crucial role in setting the conditions of capital‘s dominance as part of its hegemonic agenda. As stated by Cizre & Yeldan “privatization, flexible labor markets, financial de-regulation, flexible exchange rate regimes, central bank independence (with inflation targeting), fiscal austerity, and good governance” are the fundamental conditional elements and measures of the neoliberal agenda. The neoliberal ideology maintained its hegemony justifying the motive behind the financial liberalization with the claims of restoration of growth and stability. Nonetheless, Turkey encountered phases of financial liberalization marked by financial destructions and witnessed devastating economic crises.

The country witnessed harsh economic crises in the post 1980‘s which had severe economic and social consequences. “At the beginning of 1994, the Turkish economy found itself in a very severe financial crisis which, in turn, hit the real economy. The Turkish lira depreciated by almost 70 percent against the US dollar in the first quarter of 1994. The Central Bank heavily intervened in the foreign exchange market, and as a result, lost more than half of its international reserves” (Fatih Özatay 2000).

The “painful experiences of transition to the hegemony of international financial capital” in the period of 1989-2002 (Korkut Boratav 2004), short-term cycles of instability and growth instability in the 1990s and 1994 economic crisis were followed by the 2001 financial crisis. The 2001 crisis severely hit Turkey and worsened the conditions by deepening and continuing in the following years (Ümit Cizre & Erinç Yeldan 2005). Official wisdom explained the crisis as a “result of a set of technical errors or administrative mismanagement unique to Turkey” (Ümit Cizre & Erinç Yeldan 2005). Nonetheless, the crisis was a “result of a series of pressures emanating from the process of integration with the global capital markets” contrary to the official explanations.

The economic and financial crisis that hit Turkey in 2001 was severe in many aspects (Orhan Pamuk 2014). The Turkish government invited Kemal Derviş, who had been working in the World Bank to take the job of the Minister of Economy. This attempt has resulted in the development of an economic program with IMF support. “The program adopted a floating exchange rate regime and converted the outstanding liabilities of the public sector banks to long-term public debt. It also featured some long-term structural reforms, including measures to reform the vulnerable financial system, and a series of laws that attempted to insulate public sector banks and state economic enterprises from the interference of politicians and strengthen the independence of the central bank.” (Orhan Pamuk 2007).

Meanwhile, the Justice and Development Party (AKP) was founded in 2001. AKP‘s campaign in the 2002 elections suggested “that the party would remain within the bounds of the IMF program as well as devote more attention to social policies, in particular, poverty and unemployment” (Marcie J. Patton 2006). In the November 2002 elections, AKP and CHP passed the 10 percent threshold to enter the parliament. AKP received one-third of the votes by 34.28 percent, CHP won 19.39 percent of the votes, and 45 percent of the votes were not represented in the parliament. It further meant that AKP could form the “country‘s first single-party government in a decade”.

The relationship between the businessmen and the state can be traced in the functioning of cultural and artistic establishments that were formed in association with three businessmen, namely Vehbi Koç, Sakıp Sabancı, and Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı. These top 3 conglomerates in Turkey benefited disproportionally from the improvements in the macroeconomic environment and have become transnational in their operations.

* relationship between the growth of their businesses in the form of large conglomerates and their engagement with culture and arts.

*they are the subjects who first thought about the possibility of founding a private museum under the framework of philanthropic foundations.

*the private museums were founded in relationship with these key businessmen.

*private museums are synergic institutions to the respective conglomerates and philanthropic foundations.

Some conservative capital owners appeared as new actors in the field of arts, by collecting practices and sharing their interest in building private art museums. The recent proliferation of enthusiasm of businessmen in supporting arts is also related to Istanbul‘s rise as the “center of culture and arts”.

Globalizing Istanbul

Istanbul is the major setting for the flourishing of private cultural and artistic institutions. The social, political, and economic dynamics that have made Istanbul the center of culture and arts in the post 1980‘s will be explored. Also will be focusing on the significance of AKP in particular to explore the roots of its cultural policy orientation towards the global-city project and branding the city.

Asu Aksoy (2008) argues that “the project of globalizing Istanbul, turning Istanbul into an internationally competitive city attractive to investors, businessmen, and tourists, is now being fully realized” - a new round of urban globalization - is not only primarily driven by real-estate but also it is a cultural project too. With the opening of Kanyon shopping mall demonstrating the incorporation of public space into the culture of hyper-consumption, the Beyoğlu Municipality‘s initiative of regenerating the city quarter of Algeria Street into French Street and commercializing it and recent undertakings of conglomerates that turn culture into a business opportunity. She states that “the opening of the cultural field is underwritten by the gentrified class-base of the neoliberal regime. Cultural liberation progresses in the direction of what suits the needs of the rising elites of the city, in ways that respond to their expectations of higher living standards”.

Sibel Yardımcı (2007) discusses the recent developments in Istanbul‘s cultural scene, namely the "expansion of the events organized by the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV), the mushrooming of art galleries and publishers supported by banking companies, successive openings of universities and museums owned by large capital groups and the multiplication of other smaller scale private/semi-private artistic initiatives.

AKP is an important factor in the implementation of the project of globalizing Istanbul (Aksoy 2012). Before elaborating on AKP‘s role in globalizing Istanbul, I want to briefly note the connection of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the founding leader of the party, with Istanbul before he came to power as the Prime Minister. Erdoğan was the Istanbul candidate of the Islamist Refah Partisi (Welfare Party) during the 27 March 1994 municipal elections. He was elected as the Mayor of Istanbul in 1994 and he served for the Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality until 1998.

According to Bartu (1999), the resurgence of the Ottoman past and Istanbul is an important element of the Islamist discourse. “As a movement that challenges the Turkish nationalist project (which defines itself in opposition to the Ottoman past), the Islamic movement attempts to revitalize and resurrect the past. (…) The Islamist aim is to resurrect the lost “glorious Ottoman past.” Istanbul, the glorious capital of the empire, is a key symbol of this revival.” The Welfare Party was the only party that did not embrace the global city project. And the elections in the municipality of Istanbul and the district of Beyoğlu which was recognized as the symbol of Westernizing reformers and the entertainment center of the city by the secularists, were won by the Welfare Party. It was followed by different strategies by the Welfare Party to claim Beyoğlu back and gave way to political battles.

Tanıl Bora (1999) in his work “Istanbul of the “Conqueror The Alternative Global City Dreams” of Political Islam” argues that within the Islamic discourse, Istanbul “is believed to be lost, divorced of its true essence because of its experience of westernization” thus it “needs to be conquered again”. Bora states that this theme came on the agenda in 1953, on the five hundredth anniversary of the Conquest of Istanbul by Fatih Sultan Mehmet. Thus, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan came to power to transform Istanbul into the object of Islamic nostalgia and to remake it in the original Conqueror‘s image. Although Erdoğan distanced himself from the global city project during the respective elections, his attainment of power changed his rhetoric towards the logic of economic rationality and towards thinking about the city as a business enterprise. “Istanbul is the key to WP‘s bargain with the established structures of power primarily because the city is the locus of capital. As the Islamist movement seeks to come to an understanding with the Turkish bourgeoisie, it also has to accept the global-city project of big capital” and Welfare Party‘s developmentalist heritage and focus on industrialization drew the party towards embracing the global-city project. However, the global-city project was internalized by the Islamic politicians with an addition of alternative signification that fits an Islamic or neo-Ottoman hegemony over the region. Aksoy states that the commitment and consensus between the urban and the central government to turn Istanbul into “Turkey‘s global power base”. “The consequence of Istanbul being governed by an AKP administration has been the emergence of a total accord between central and local governments” between Ankara, where the central government is seated, and Istanbul, which is being promoted to the global stage.” It is crucial to note that exploiting Istanbul‘s potential for culture and tourism reached its climax when Istanbul became the European Capital of Culture in 2010. Istanbul European Capital of Culture Agency (NOW CLOSED) was set up by law and making Istanbul a ‘brand city’ was the key objective of the Agency, in the framework of the Istanbul 2010 program both the urban and central governments were committed to the restoration and regeneration of the city‘s rich cultural heritage and this was supported by a controversial new law on ‘renewal’ of historic areas. Most importantly, however, while Istanbul has been transformed and opened to market-driven global forces under the state-led project, the social divisions escalated and urban public culture has been increasingly privatized:

“The prevalence of neoliberal values within the Islamic AKP (Justice and Development Party) government, over the last decade or so, is associated with this more assertive, globalizing, and entrepreneurially minded Istanbul. As global processes increasingly, and seemingly irreversibly, affect the daily life of the city‘s 15 million residents, older modes of urban living and established forms of public culture are damaged, if not devastated. This represents one contemporary variant of world-openness-the neoliberal articulation. Openness to global economic forces is associated with escalating social divisions, existential loss of control, increasing privatization of urban public culture, and the end of Istanbul as we know it (Aksoy 2012)”

The shift in Recep Tayyip Erdoğan‘s stance towards the aspirations of big capital can be demonstrated by one particular ironic case which is directly associated with the subject of this dissertation. In the late 1980s, the idea of building a modern art museum emerged in IKSV and Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı. It was declared to the public that the Feshane would be renovated and turned into a museum with the contributions of Eczacıbaşı Family. Efforts were made in this direction including the renovation of the building by Gae Aulenti with huge financial support from the Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı. Nonetheless, the project was canceled due to the friction between the initiators and local government when Recep Tayyip Erdoğan became the Mayor of Istanbul Metropolitan Municipality. [It was Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, who supported and enabled the establishment of the Istanbul Museum of Modern Art in Istanbul in 2004, initiated by the same capital group.] Alongside AKP, corporations, and corporate actors have become the conveyors and crucial actors of Istanbul‘s transformation in a neoliberal and global direction. United under the umbrella of attracting capital and globalizing Istanbul, various capital groups engaged in activities and events supporting culture and arts with the aims of fostering culture and tourism. It is argued by Aksoy that the city space of Istanbul has been mobilized for market-oriented economic growth and elite consumption practices and this transformation is underwritten by the coalition of two elite groups. Two groups are “the post-1980‘s generation of secular, middle-class and professional workers” as ‘North-Istanbul elites’ and “the rising commercial elites of the Islamic-oriented traditional circles, politically represented by the ‘innovative group’ in the ruling AKP”.

Legal Framework Enabling Privatization in Culture

The legal framework enables private entrepreneurship, corporate sponsorship, private investments, and the establishment of private museums in art. Exploring the characteristics of cultural policies and their relevance with the expansion of interest in culture and arts.

AKP governments have instrumentalized culture and arts to enhance the “image” of Turkey within the global markets and Istanbul has been the center of this operation. In this context, within the last decade, corporate sponsorship of private investments in culture and arts, and the establishment of private museums are supported by the laws and regulatory changes. One of the crucial aspects to consider is the taxation policies. Furthermore, the rhetoric on privatizing state cultural institutions and the draft bill shall be evaluated within this context. I will briefly discuss the legal and regulatory framework which I consider important for building the infrastructure for the intervention of non-state actors in the field of arts and culture; thus, enabling the increasing privatization of culture.

The legal framework constituted by Law No: 5225, Law No: 5422, and Circular in 2005 and Regulation on Private Museums and Supervision is directly related to the subject. One of the most important items to be considered in Law No: 5225 is the incentives granted to the subjects who financially support culture and arts. The incentives provided by this law are income tax withholding deduction, allocation of immovable property, abatement in employer contributions, water cost discount and energy support, ability to employ foreign personnel or artists, and ability to function on weekends and official holidays. Another important item to be considered introduced by this Law is the tax exemption to be granted to investors in arts and culture. Although it is not clear whether the investors in Turkey benefit from this law or not (Kösemen 2014) it provides tax deductions and applies incentives for those who intend to invest in arts and culture. Tax incentives are also granted to sponsors of culture and arts. On 14 July 2004 legislation was enacted. Law No: 5422 amending Decree Having Force of Law No:178 and Some Other Laws.

The sponsorship as a corporate act comes along with the legal framework that determines how corporations can act. Cultural sponsorship has been transformed into an appealing activity within the context of legal and regulatory initiatives in the AKP Era. The lucrative character of sponsorship cannot be reduced to the advertising of the sponsors; its instrumentalization for social recognition and prestige. Rather, if one considers the economic benefits of cultural sponsorship, state incentives, and tax advantages should be recognized.

Private Initiatives in Arts

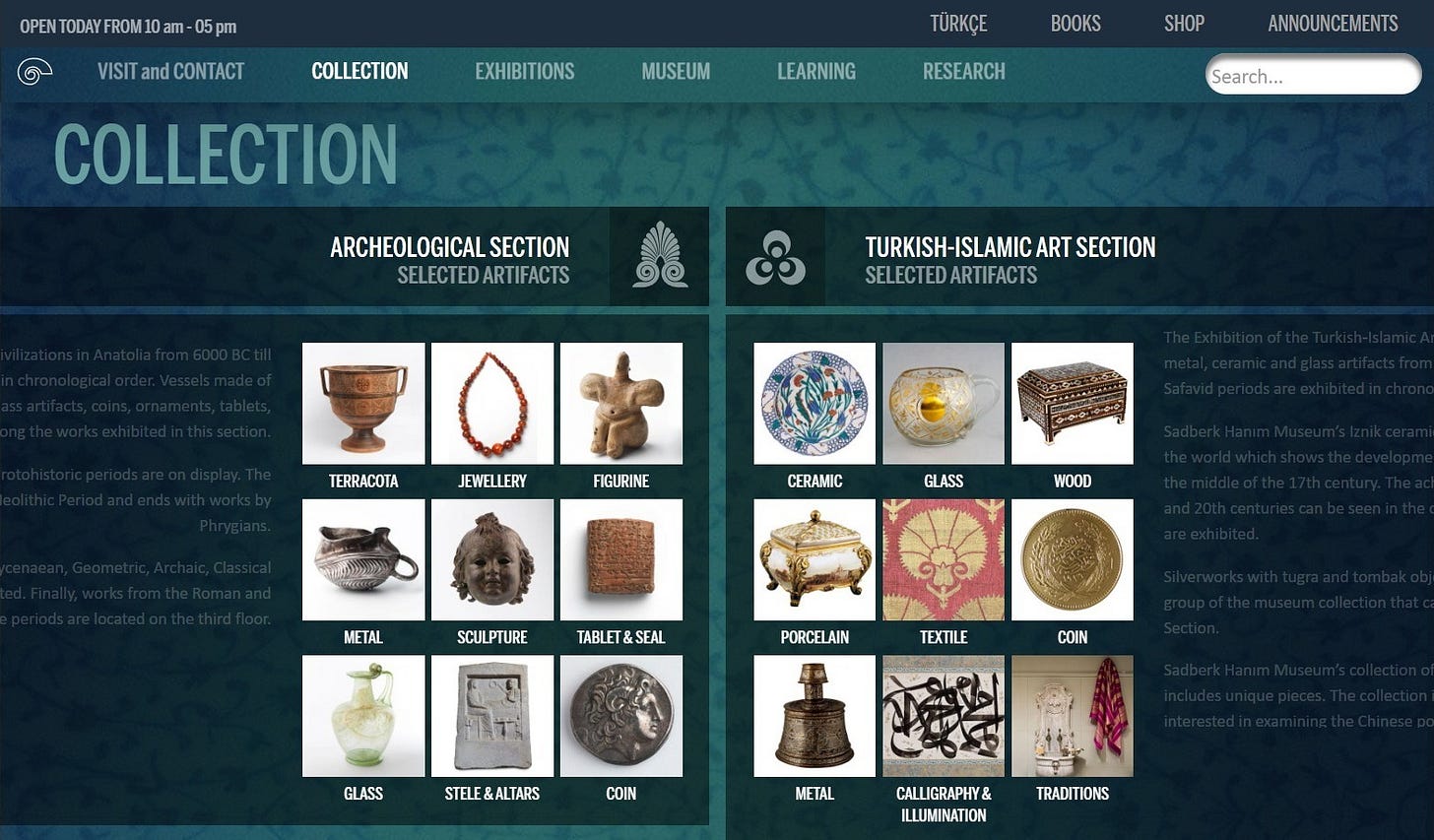

*In 1980 the first private family museum Sadberk Hanım Museum was opened in Sarıyer, Istanbul by Vehbi Koç under the framework of Vehbi Koç Foundation.

*In 1981 Ziraat Bankası Müzesi (Ziraat Bank Museum) was established at the headquarters of the bank in Ulus, Ankara.

*In 1985 Yaşar Eğitim ve Kültür Vakfı Müzesi (Yaşar Education and Culture Foundation Museum) was founded in Izmir.

*In 1987 1st International Istanbul Contemporary Art Exhibitions was initiated by IKSV. It transformed into the International Istanbul Biennial and respectively 2nd Istanbul Biennial was organized in 1989 and continues still today.

*In 1993 Aksanat Beyoğlu was founded in Beyoğlu, Istanbul. Ziraat Bankası Tünel Sanat Galerisi (Ziraat Bank Tunnel Art Gallery) was founded in 1999 in Beyoğlu, Istanbul.

*In 2000 İş Sanat Kibele Sanat Galerisi (İş Sanat Kibele Gallery) was opened in Istanbul as İş Bank‘s initiative. Platform Garanti Güncel Sanat Merkezi (Garanti Platform Contemporary Art Center) was founded in 2001 in Beyoğlu as Garanti Bank‘s initiative.

*In 2001 Proje 4L İstanbul Güncel Sanat Müzesi (Project 4L Istanbul Museum of Contemporary Art- NOW: ELGİZ Museum) was founded by the collection of businessman Can Elgiz.

*In 2002 Sabancı Museum was established under the framework of Sabancı University founded as Sabancı Foundation‘s university.

*In 2002 Ottoman Bank Museum was founded by Garanti Bank in Istanbul.

*In 2003 Garanti Bank established Garanti Gallery in Beyoğlu, Istanbul.

*In 2004 Istanbul Museum of Modern Art was founded as Eczacıbaşı Holding initiative.

*In 2005 Suna and Inan Kıraç Foundation established Pera Museum in Istanbul.

*In 2007 Santralistanbul Museum was founded as an initiative of Istanbul Bilgi University.

*In 2007 Rezan Has Museum was opened under the framework of Kadir Has University.

*In 2010 Arter was founded in Beyoğlu by Vehbi Koç Foundation as a contemporary art platform.

*In 2010 Cer Modern Art Center was founded in Ankara as an initiative of the Association of Turkish Travel Agencies.

*In 2011 SALT was founded by Garanti Bank and former Garanti Bank institutional initiatives were incorporated under the framework of SALT. Currently SALT has three branches SALT Beyoğlu, SALT Galata in Istanbul, and SALT Ulus in Ankara.

*In 2011 Borusan Contemporary was opened in Istanbul at the Perili Köşk, the headquarters building of Borusan Holding based on the contemporary artwork collection of the holding.

THE ORIGINS OF PRIVATE ART MUSEUMS: KOÇ, ECZACIBAŞI, AND SABANCI FAMILY FOUNDATIONS

This section explores the complicated relationship between capital and the arts and culture by focusing on three interrelated aspects: first, the peculiarities and social class positions of businessmen and their family members, their cultural preferences and interests in art, and foundations as institutional forms and manifestations of their cultural interests. Not only the relationship that the foundations have with the founders is given importance, but also the roles of foundations in making cultural institutions, forming an art market, and developing cultural industries are explored.

The founding of private initiatives in art and the institutionalization of cultural and artistic activities are better understood regarding the developments in the business environment. The influence of key figures, the founders and first-generation executives of big businesses in Turkey, play crucial roles in taking the first initiatives that set the rules and ways of institutionalization for further initiatives in the arts and culture. Consecutively, this section tracks the origin of ideas, and conceptions concerning the development of ―philanthropic activities “undertaken by Koç, Sabancı, and Eczacıbaşı Holding Companies by focusing on the autobiographies written by Vehbi Koç, Sakıp Sabancı, Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı and Şakir Eczacıbaşı and key developments in their institutionalization in the form of foundations. Vehbi Koç, among other Turkish businessmen, can be considered a pioneer in terms of his role in constituting the legal and institutional framework of the commercial as well as social activities that are carried by Turkish businessmen in Turkey. Vehbi Koç was born in 1901 (Koç 1973), Ankara and wrote two autobiographies: Hayat Hikayem (My Life Story) in 1973 and Hatıralarım, Görüşlerim, Öğütlerim (My Memories, Visions and Advice) in 1987. The first autobiography written in the early 1970s not only precedes the autobiographies of Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı Kuşaktan Kuşağa (From Generation to Generation) written in 1982 and Sakıp Sabancı İşte Hayatım (This is My Life) written in 1985 but also constitutes the very first example of an autobiography of a businessman written to transmit his own life stories and business experience as a case of ―success” to future generations.

The foundations focused on this section are Vehbi Koç Foundation (VKV), Sabancı Foundation (SF), Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı Foundation, and Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV). These foundations, except the IKSV not necessarily established for the sake of endowment to culture and arts. Yet, they share the common characteristic of being initiated by individual actors who had found large family conglomerates in Turkey. The section discusses the peculiarities related to their establishment (founders, the relationship between the founders and the state, inspirations) meanings, and values attributed to these institutions by their founders and the society by the time they emerged. Furthermore, the foundations that are considered here, are relevant to the establishment of initial foundation museums in Turkey, as well as closely associated with the establishment, functioning, administration, and funding of the cases (Sabancı Museum, Pera Museum, Istanbul Modern Museum) of this thesis in various ways.

*Vehbi Koç-“The Father” of Private Sector

Vehbi Koç was born in 1901 and he was the founder of the Koç Holding Company and often represented by his self-disciplined, programmed, and distant personality (Can Kıraç 1995) and his life experience which spans over ninety years that witnessed both the last decades of the Ottoman Empire and the firsts of Republic of Turkey. His life and the development of his business experience overlap with the history of modern Turkey. He was not an educated man but rather considered a “self-made” man and regarded as a perfect example which reflects the making of new businessmen under the conditions of Republican Turkey (Ayşe Buğra 1994, p.76-77) regarding his business life that started as a son of a grocery shop in Ankara and turned into one of the prominent figures in the Turkish capital by receiving the advantages of the Ankara as a growing capital of modern Turkey and opportunities provided by respective government projects. While his business activities include involvement as a contractor in government projects, importing and distributing oil, gas, and motor vehicles during the 1920s, during World War II, he began importing trucks for the government at a high commission percentage, and in the aftermath of the War, he undertook projects within the framework of Marshall Plan which was regarded as a turning point in his business life. Although he was politically affiliated with the Republican People‘s Party during the early years of the Republic, in the 1950s he resigned the party with the enforcement of the governing Democrat Party. During that time, the Otosan factory was established to serve the assembly production of Ford vehicles. Although the company remained mostly based on commercial activities rather than industrial ones until the 1950s, by the time foreign exchange shortages were severe, the company was directed to industrial ventures. By the 1960‘s his business was expanded with diversification in the business activities in many sectors.

One crucial organizational change that Koç Enterprises faced was the formation of a holding company in 1963 for the need for organizational restructuring with the growing number of educated family members assuming managerial positions in the company, in addition to the difficulty that was faced with the expanding scope of activities (Buğra 1994, p.77-82) that in addition to the diversification of activities, the acquisition of real estate is also an important characteristic of entrepreneurship in Turkey, which underlines the reason and rationale behind; the call for financial security and flexibility under the uncertain conditions.

One other important characteristic that Koç Holding has held since its founding years, has been its affiliations with foreign companies. During the early years of the company, this was reflected in the company‘s receiving the representative rights of foreign companies in Turkey. While Ford and Standard Oil constitute the first two crucial examples in the company‘s history in this line, a joint venture established by General Electric Company in 1948 to build a light bulb factory in Turkey, which started production in 1952, can be counted as another important example.

International business activities have appeared to remain an important aspect of the company since then; now the company has foreign partners in different sectors from countries including Italy, the USA, South Korea, Great Britain, and Poland. The company has an international network of 24 countries either by group companies or representative offices, including Australia, Germany, Egypt, Spain, France, Italy, Slovakia, China, France, Russia, Ukraine, South Africa, Austria, United Kingdom, Singapore, Romania, Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Czech Republic, Iraq, Algeria, Netherlands and Poland. Now, the Koç Group Company defines itself as “The Largest Investment Holding Company in Turkey”, and promotes itself with its reputation in the Fortune 500, as being the “only Turkish Company” in the respective list, has 70 companies dispersed in energy, automotive, consumer durables, finance as the major areas of activity and has established companies in construction, tourism, food, information technologies, defense technologies, advisory, retail, air transport and services, marketing, and logistic sectors (Koç Holding Activity Fields, n.d.).

Alongside his economic personality which was crucial for the establishment of one of the largest conglomerates in Turkey, the engagement of Vehbi Koç in social affairs as well as the initiatives that were taken in his lifetime worth considering for tracing back to the company‘s investments in arts and culture.

Vehbi Koç was a middle school dropout who started business at an early age, first by assisting his father in his small enterprise in the 1910s, (Koç, 1974) later in the 1920s after having his first encounters with the merchants and businesses in Istanbul and his arranged marriage in 1926 with his cousin Sadberk Hanım, he took over his father‘s business in 1926 and registered the firm after his name as Koçzade Ahmet Vehbi. He had become an ‘industrialist‘ during his business life which was marked by the establishment of his first enterprise as a trading company later transformed into an incorporated company in 1938 and became the first holding company in Turkey in 1963.

The review of Vehbi Koç‘s life history illustrates the case of economic capital accumulation and reveals the importance of his early socialization in his perceptions, aspirations, and practices an accumulation of social and cultural capital throughout his lifetime. Furthermore, one of the guiding main aims of this task undertaken here is to figure out how the actors, Vehbi Koç in the first instance here, in concern produce and reproduce their social positions and constitute a field through the struggle over the appropriation of economic as well as cultural, social and symbolic capital.

The prevalent themes appear as mostly as “aims” and “visions” in Vehbi Koç‘s autobiographies. These prevailing themes form the basis of his thinking and are presented to be the underlying intentions in his business and social practices. The concepts of müesseleşme (institutionalization), profesyonelleşme (professionalization), and devamlılık (permanence) are particularly important and have attributed positive connotations throughout both autobiographies written by Vehbi Koç and assigned with the value of success if maintained and power of legitimization to both economic and social activities carried on. The main themes that appear in Vehbi Koç‘s narrative are the importance of institutionalization, ensuring prevalence in business, emphasis on the unity of the family and its importance in realizing the mentioned aims, the importance of the professional administrative body, the importance of well-educated and qualified staff in business in particular and in society‘s development in general. Furthermore, the existence of the private sector has been advocated in various ways in his autobiographies by gaining its legitimacy through the emphasis on the criteria mentioned above, namely, institutionalization, professionalization, education, and unity of family, besides the emphasis on the roles associated with the private sector. One of these crucial roles attributed to the private sector is the provision of democracy. He states that he believes in the following statement (Koç 1987, p.80): “If there is a private sector in a country, there is democracy in that country”.

“The private sector was born and has grown during my working life and it has gained its identity today. I consider her as my child. This assigns me some rights. I transmit my experiences to young people on every occasion, to avoid the repetition of mistakes and for evermore internalization of the role of strengthening the economy. Therefore, I am aware that I act a bit preachingly. Nonetheless, I am writing my book with such an aim.”-Vehbi Koç.

Vehbi Koç prioritizes education and health as two important fields to locate his social activity as the first areas dating back to the 1950s. For instance one of his very first initiatives was to establish a student dorm for Ankara University in 1950. This example not only reflects the effect of American influence on him, by choosing a university student dorm over building a mosque in Ankara but also underlines the importance of legal framework and the relationship with the political power in the making of intended institution models in Turkey. The construction of the dormitory, developed based on the idea of the Rockefeller Student Dorm in New York City, was completed in 1950 to deliver to Ankara University, according to the law enacted in 1949 that accepts the unification of whole universities under the body of Ministry of Education, an obstacle appeared for Vehbi Koç to donate the dorm to the administration of University. While he insisted on donating the dorm to the management of the University to avoid the political peculiarity of the Ministry, in 1950, the Democrat Party won the elections and Adnan Menderes became the Prime Minister of the country, who then accepted the request of Vehbi Koç and in 1951 a new law was enacted that provided the required basis for the administration of granted or bequeathed dormitories by the Universities. Furthermore, in due course, Vehbi Koç met Celal Bayar, the then President of Turkey on an occasion and requested him to open the dormitory which was rejected by Bayar due to the controversial political stance and position of Koç at the time.

The reason why this case is pointed out is to demonstrate how members of economically powerful families such as Koç, Sabancı, and Eczacıbaşı have encounters with the political authorities and state institutions while actualizing their social initiatives. Similar encounters are observed in the cases of private art museums, which have both negative and positive effects, from the perspective of the actors, varying from museums‘ founding to the promotion through their activities and ceremonies, as well as in cases such as the establishment of international partnerships.

-Vehbi Koç’s Sadberk Hanım Museum

The location of the museum was decided in the late 1970s by the Koç Family and one of the estates of Vehbi Koç, located in Sarıyer, Istanbul named the Azeryan Yalısı [Azaryan Yalısı was built in the early 1900s by Merchant Bedros Azaryan and bought by Vehbi Koç in 1950 and was used as a summer house by the family until 1978. It was renovated and restored regarding a Project by Sedat Hakkı Eldem.] was chosen to be the museum space. The building was renovated and opened as the Sadberk Hanım Museum on October 14, 1980, by the then Minister of Culture Cihat Baban. This case is important to demonstrate how real estate investments turn into cultural investments.

“It is stated that 25 million lira was spent for the restoration of the museum and the value of the exhibited collection is way beyond the money spent. Besides, the Koç Family has generated a special fund for meeting the expenses of the museum (Cumhuriyet Newspaper, 14.10.1980).”

The museum collection was not centered around a theme, a specific genre of art, or a specific period in history, rather it was scattered around silver objects, jewelry, ornaments, objects from 16-18th century Turkish handiwork, Iznik tiles and pottery, Turkish traditional garments, objects from different historical periods and different civilizations including bronze age, Hittite, Frig, Greek, Hellenistic, Roma, Seljuk, Byzantium and Ottoman (Koç 1987, p.164). It is seen that the museum was recognized as an exhibition place for the family. The founding of Sadberk Hanım Museum was based on the collection of Sadberk Koç as mentioned above. The idea of the museum not only emerged from her collection of antiquities and her wish to be remembered but also she was represented as the source of inspiration and the key figure as the source of interest in the antiques in the Koç Family. Sadberk Hanım Museum underlines the significance of the Koç Family and serves as an extension to the economic acquisitions, whose role is to publicize the power of being prevalent. The main interest behind such an establishment was manifested as the intention of keeping the family name persistent, through remembrance of the initial collector Sadberk Hanım, and providing an opportunity for the rest of the community to enjoy what had been owned, the implicit interest was the symbolic capital acquired through this manifestation, which is the source of power.

The importance of family and its members is emphasized in Vehbi Koç's narrative. Family plays a crucial role in various aspects, such as accumulating cultural capital through education in esteemed institutions across generations. Furthermore, it is argued that family serves as a legitimate foundation for many of Koç's ventures and plays a pivotal role in shaping the relationship between the Koç Family and the realms of culture and arts. Primarily focusing on the Sadberk Hanım Museum and its establishment, exploring the mechanisms behind its creation and its validation as the pioneering family museum of a wealthy Turkish family. Additionally, the involvement of women within the family as influential figures in the arts, particularly concerning the establishment of museums like the Pera Museum, Sabancı Museum, and Istanbul Museum of Modern Arts is explored. This sheds light on the gendered division of labor and its significance in understanding various cultural institutions.

The collection was gathered through acquisitions and donations, making an exhibition space a legally recognized “private museum” that has been strongly associated with the laws and regulations that bind such a foundation. At this point, the state institutions, laws, and regulations intervene and the main state actor to address is the Ministry of Culture.

* Sakıp Sabancı –The Social Man

Sakıp Sabancı was born in 1933, in a village in Kayseri as the second oldest son of Sabancı Family. The Sabancı Family moved to Adana in 1921 where Hacı Ömer Sabancı started working as a cotton trader. His business developed by becoming a shareholder in a cotton ginning plant, and later becoming a shareholder of a vegetable oil plant in the 1930s and 1940s. Some of the important companies founded by Hacı Ömer Sabancı until his death in 1966 were the Akbank in 1948, Bossa Flour in 1950, Bossa Textile in 1951, Oralitsa Construction Materials, Aksigorta Insurance Company in 1960.

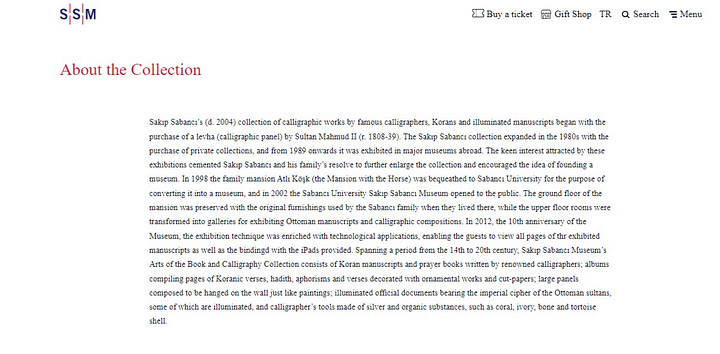

Sakıp Sabancı was raised in Adana and studied until his high school years, which he could not finish due to his health problems and left the school in 1950 meanwhile he was trained in his father‘s business. At the age of 24 in 1957 he got married to his cousin from his mother‘s side Türkan Civelek and became the father of three children: Dilek Sabancı born in 1964, Metin Sabancı born in 1970 and Sevin Sabancı born in 1973. In the aftermath of his father in 1967, Hacı Ömer Sabancı Holding was founded. Sakıp Sabancı was elected as the first Board of Directors among his brothers. He served as the President of Sabancı Holding from its establishment in 1967 to his death in 2004 (Sakıp Sabancı Official Website, n.d.). During his presidency, Sabancı Holding has been expanded with joint ventures with transnational companies such as Bridgestone, DuPont, Toyota, Philip Morris, Kraft Foods International, Danone, IBM, and Carrefour as well as operating and marketing its products worldwide (The Sabancı Group in Brief, n.d.). Currently, Sabancı Group companies operate in 18 countries and market their products in regions across Europe, the Middle East, Asia, North Africa, and North and South America in 2013 the consolidated revenue of Sabancı Holding was TL 24.2 billion (US$ 12.7 billion) with operating profit of TL 4.9 billion (US$ 2.6 billion). The Sabancı Family is collectively Sabancı Holding‘s major shareholder with 57.7% of the share capital. “Sabancı Holding‘s consolidated revenues rose by 25 percent to 13.48 billion Turkish liras year-on-year in the first half of 2014. In the same period, the holding posted consolidated net profit of 979 million Turkish liras and non-bank consolidated operating profits of 465 million Turkish liras, with a 35 percent rise year-on-year Sabancı Holding‘s total assets reached 220.39 billion Turkish liras and total consolidated shareholders‘ equity 18.27 billion Turkish liras as of June 30, 2014.” (Sabancı Holding Press Release, 15.08.2014).

The Sabancı Group operates in various business units such as energy, banking, insurance, cement, retail, and industrials as well as has been associated with Sabancı University and Sakıp Sabancı Museum through the Sabancı Foundation.

Sabancı Foundation was founded in 1974 by the members of the Sabancı Family in, an attempt to institutionalize their philanthropic activities and address the members of the family as the “prominent figures in various charitable initiatives‖ while stating their mission: "To promote social development and social awareness among current and future generations by supporting initiatives that create impact and lasting change in people's lives" Currently, The Sabancı Foundation presents its scope of activities as building institutions (Sabancı University, educational institutions, dormitories, teachers centers, health care centers and hospitals, libraries, sports facilities, cultural centers, social facilities) in addition to contribution to other institutions and non-governmental organizations, providing scholarships, giving awards in education, arts and sports, supporting festivals and contests in the sphere of arts and culture and programs developed with the “aims to enable social inclusion by promoting an equitable environment in which women, youth and persons with disabilities have access and equal opportunities to actively participate in society”.

As in the case of Vehbi Koç‘s presentation of foundation, Sakıp Sabancı was aware of the foundations in the United States of America, yet emphasizing the Ottoman roots of philanthropic giving serves him a kind of legitimization that suggests that, this is not new, we already had this in our tradition and our history. Contextualizing the foundation in a historical as well as religious axis allows him to conceptualize the foundation as an old phenomenon that was recognized while separating the role of the private sector and the material interest embedded in establishing this organizational form.

Other sources of inspiration and motives appearing in Sabancı‘s narrative are also interesting to reveal the “interested” character of his philanthropic pursuits. First, he refers to his family‘s understanding of philanthropy by exemplifying it through his father, mother, and brother engaging in philanthropic activities and charity work, especially on religious occasions such as Bayram (feasts) besides ordinary days. This serves to emphasize that these philanthropic practices had existed in the “family” and his ancestors and tradition before this organizational form and asserts a status to the family. On one hand, it associates the family with philanthropic activities, and on the other; it separates the sphere from economic interests in gaining profit and expanding the business.

Sakıp Sabancı had neither been exposed to higher education nor got acquainted with the arts during his family socialization. His only reference was his father, who started collecting antiques in his old age and was described by him as an “Anatolian man”, self-educated, trade-oriented, and characterized as a frugal personality:

”Everyone knows about my father‘s lifestyle and his poverty in his initial years. However, the interesting thing is this. When he moved on to industry and developed his business, my father suddenly started to be interested in works of art, which was not very normal in those times. Since he did not have any expertise on it, he found someone who did. For example, in Istanbul, father Portakal was my father‘s consultant. My father made him buy paintings, vases, and sculptures. He did not keep away from paying for these. He collected those works of great value that reside in our Emirgan House now, like this (Sabancı 1985, p.291).”

Sakıp Sabancı, in his autobiography, refers to his father‘s practices in his old age as “My father often visits his friends in government offices or wanders in the antique shops in Istanbul, collecting antiques” (1985, p.93) Unlike his father, who collected European artists work, by the consultancy of Portakal, Sakıp Sabancı described his interest in art as focused on Turkish work of arts (p.291). His evaluation of his interest in arts divided into three stages first he collected the “well-known” paintings of Turkish painters then collected Turkish artists‘ calligraphies, and then his interest shifted towards the handwritten Qurans, tesbih, marble fountains, and sculptures (p.291-292). Various sources of inspiration led him to collect calligraphy, handwritten Qurans, and tesbih. His interest and taste in the respective forms of objects developed over time and through his encounters with experts in the field. This is important because Sakıp Sabancı acquires knowledge of forms of Islamic arts and Turkish painting through his acquaintances. In this respect, his social capital in addition to the economic capital enables him to accumulate cultural capital over time. It appears as an effort to increase the volume of cultural capital to struggle for power and status, among the dominant classes. Bourdieu (1984) argues that there are differences among the same social class concerning the volume of different forms of capital and cultural capital in this respect is the crucial form of capital that constitutes the social status differences among individuals. In Sakıp Sabancı‘s case, the lack of educational attainment as well as the upper-class way of life and cultural practices during his early socialization have led to the conversion of economic capital and social capital into cultural capital in his later years through expanding his knowledge on arts and forming collections.

*Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı-The Cultivated Man

Eczacıbaşı is one of the leading industrial groups in Turkey with 41 companies and over 12,000 employees and a net turnover of 6.7 billion TL in 2013 (Eczacıbaşı Group Profile, n.d.). The founder of the group is Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı (1913-1993), who was born in Izmir and son of Süleyman Ferit Bey. Süleyman Ferit Bey was a pharmacist in Izmir and was the first university-educated pharmacist in the city and distinguished himself with a long career of public service during the early years of the Turkish Republic (Eczacıbaşı Group Founder, n.d.). He was given the honorary title and then surname of Eczacıbaşı, meaning “chief pharmacist” in recognition of his continual efforts to improve the health of his community.

After graduating from Robert College [based in Istanbul, which only the privileged students could attend, he not only interacted with the American culture through the extensive education program of the college and its foreign instructors (Eczacıbaşı 1982, p.26-34) but also developed the skills of foreign language capability that further provided him a higher status where the knowledge of English is itself a source of social distinction in Turkey, at the time being. Access to the respective education institutions, as well as the habitus, as Bourdieu uses the term, is crucial for constituting his social position and status.] Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı completed his undergraduate degree in chemistry at Heidelberg University in 1934 and his master‘s degree in chemistry at the University of Chicago. Choosing biochemistry as his field of expertise he earned his PhD degree at Berlin University in 1937. Until 1939 he was an academic assistant at Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Medical Research in Heidelberg, which would be re-founded as a Max Planck Institute in 1948.

Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı returned to Turkey in 1942 and established a pharmaceutical laboratory in Istanbul, whose first product was a vitamin capsule. Following investments in ceramic products the Scientific Research and Medical Award Fund was founded by Eczacıbaşı to promote and reward successful research in the areas of medicine, chemistry, and pharmaceutical science in 1959. The group expanded its activities to health-based consumer goods, welding electrodes, and ceramic sanitary ware through the 1970s. In 1973 he led 16 businessmen and philanthropists and founded the Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts (IKSV).

In 1977 the group‘s “VitrA” brand in ceramic sanitary ware was established with its new plant in Bozüyük, Bilecik. In 1978 Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı Foundation was established to promote culture and the arts, scientific research, education, and social development. The group established the Interna brand on high-quality kitchen and bathroom sets in 1978. 1982 was the year when the group established an active pharmaceutical ingredient and parenteral solution plant in Ayazağa, which would become a joint venture with Baxter International in 1994. During the 1980s the group established the Artema brand on modern sanitary fittings and also entered to information technology industry. After 1990 when one of the affiliations of the group Eczacıbaşı Pharmaceuticals Manufacturing was offered to the public the group, the year 1992 was an important benchmark for the group with the establishment of its new pharmaceutical plant having an annual capacity of 150 million in Lüleburgaz; and also with the establishment of new international ventures with foreign companies like James River, Procter & Gamble, American Standard of USA and Marazzi of Italy. In 1996, as a result of new investments in ceramic tiles, the group‘s VitrA brand became one of the largest producers of ceramic sanitary ware in the world. Those new investments and international joint ventures in pharmaceuticals, ceramics, health care, and information technology through the 1980s and 1990s followed by the passing away of Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı in 1993.

Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı was referred to as a philanthropist in the biographical information provided by the Eczacıbaşı Holding and the man of arts regarding his philanthropic activities and practices through civil society organizations in the field of arts and culture. He engaged in civil society organizations in which he had been the leading actor behind their formation member of the board, or both. He contributed to the sphere of arts and culture by being the major initiator of the Istanbul Festival in 1973 and the establishment of Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, which shaped the art world and cultural life of Istanbul through the organization of international Istanbul Festivals diversified in music, jazz, film, theatre and making of International Istanbul Bienniale, as well as have had considerable impacts in the emergence of cultural industries and cultural actors in the aftermath of its establishment.

The aims of Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı in engaging various fields, including culture and arts presented by Eczacıbaşı Holding. It is suggested that “Throughout his life, Dr. Eczacıbaşı saw to it that every new business venture was complemented by an additional contribution to culture, science, arts and education. Today, Eczacıbaşı Holding has become a unique symbol in Turkey of the bridge that can be forged between culture and private enterprise.” “In all that he did, Dr. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı endeavored to improve the standard of life for future generations and had the satisfaction of seeing his life's achievements contribute to these high aspirations”. In this presentation however, it is claimed that “Eczacıbaşı Holding has become a unique symbol in Turkey” and Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı is addressed as the contributor in “high aspirations”. Alongside the contribution of these representations to the corporation and the social status of Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı, I am interested in how this interest in culture and arts, besides the mentioned other fields come to exist and how the rationality behind forging culture and private enterprise has been produced concerning social class and the enterprise culture.

Alongside IKSV which focused on arts and culture, Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı was also affiliated with various prominent civil society organizations (foundations, think tanks, Chambers) that specialize in business, industry, and scientific research on social and economic issues, in both administrative and founding roles. Furthermore, he was also associated with the field of education in various respects. Unlike, Vehbi Koç and Sabancı he did not prioritize and realize the establishment of a Foundation University in Turkey, yet through his visionary and initiative roles his presence had been prominent in the field of education. In the 1950s, he led the formation of the Institute of Business Economics at Istanbul University, in which professionalization of the workforce through this institution was intended, alongside his council membership in the Science in The Scientific and Technological Research Council of Turkey (Can Dündar 2003, p.96). Since the 1960s, Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı played an important role in the founding and administration of some important organizations. In 1960, he became a member of the Board of Trustees of newly- establishing Middle East Technical University and remained on duty until his resignation in 1969 (Eczacıbaşı 1982, p.147-148), while he was also the Board Member of Istanbul Chamber of Industrialists. Following the 1961 constitution, the activities in the civil society have increased. Among the consecutive developments of the period one of the important establishments that crystallized the dynamics of the time, the Economic and Social Studies Conference Board (ESEKH) was the initiative of Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı, which then gained its current institutional structure in 1994 as TESEV. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı, was also one of the co-founders of the Turkish Industry and Business Association (TÜSIAD) together with Vehbi Koç (Koç Holding A.Ş.) and Sakıp Sabancı (Sabancı Holding A.Ş.) and other businessmen from various domestic firms and conglomerates [Selçuk Yaşar (Yaşar Holding A.Ş.), Feyyaz Berker (Tekfen A.Ş.), Hikmet Erenyol (Elektrometal San. A.Ş.), Raşit Özsaruhan (Metaş A.Ş.), Melih Ozakat (Otomobilcilik A.Ş.), Osman Boyner (Altınyıldız Mensucat A.Ş.), Ahmet Sapmaz (Güney Sanayi A.Ş.), Ibrahim Bodur (Çanakkale Seramik A.Ş.), Muzaffer Gazioğlu (Elyaflı Çimento Sanayi A.Ş.).]. Moreover, Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı was the first president of the Turkish Educational Foundation, established in 1966 to provide scholarships for university and graduate students, and was a member of the Board of Directors of the Turkish Scientific and Technical Research Institute in the 1970s. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı also established a foundation dedicated to his name in 1978, namely The Dr. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı Foundation which serves by providing scholarships for talented musicians, annual cinema and graphic arts awards and grants to public schools and institutes for scientific research besides publishing books by distinguished authors and developing a collection of modern Turkish paintings.

Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı was interested in building a modern image, articulated with the Turkish national identity and gaining international recognition. The involvement in the fields of art and culture was represented by Eczacıbaşı, as part of the identity of an industrialist. The social identity of the industrialists was not only described and explained by Eczacıbaşı (1994, p.297-303) but also a prescription was provided for industrialists to build that identity.

Vehbi Koç, Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı, and Sakıp Sabancı portray different cultural interests and preferences where, exposure to class position of the family and socialization, exposure to education (foreign language education, education institutions attended) life experience abroad in European countries and the United States as well as the place of birth appear as important factors that bear on individual propensity to have an interest in arts and cultural preferences. The upper classes in Turkey do not constitute a homogeneous entity and are divided into distinct fractions about their cultural and educational background. The internal distinctions especially among industrialists and high-level executives, especially in the first and second generations of the family enterprises, about their cultural preferences are important markers of status differences, where educational credentials appear to be important instruments in this regard (DiMaggio & Useem 1978).

There are cultural differences among the upper strata of society in terms of educational background, cultural and artistic taste, and lifestyle. By looking at the three key figures who knew each other by the 1960s and onwards joined each other for certain causes such as the establishment of TÜSIAD, the founding of the Turkish Education Foundation, and some activities of ESEKH (Eczacıbaşı 1982, p.157) and hold an opinion about each other, as well as having an experience on each other in terms of business activities and social causes, Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı stand out among the other two actors, with his urban and well-educated background in well-established European and American schools and way of life with high cultural and artistic taste compared to Vehbi Koç and Sakıp Sabancı. Most importantly his lifestyle and cultural tastes that were shaped by his cultural socialization as well as social and cultural capital not only placed him in a distinct place in the society but also among the other businessmen, as in the case of Vehbi Koç and Sabancı. I suggest that both of the actors admit their differences, produce, and reproduce by neutralizing them in certain ways.

Currently, Vehbi Koç Foundation‘s art and cultural initiatives include: Sadberk Hanım Museum, Vehbi Koç and Ankara Research Center (VEKAM), Koç University's Research Center for Anatolian Civilizations, Koç Family Galleries on Ottoman Art at the Metropolitan Museum initiated in 2011, Vehbi Koç Foundation Contemporary Art Collection (initiated in 2007), Contemporary Art in Turkey Monograph Series at Yapı Kredi Publishing (2007-2011), ARTER-space for art 2010, TANAS (contemporary art space in Berlin initiated in partnership with Edition Block Berlin in 2008). The projects supported by the Vehbi Koç Foundation include the Venice Biennial Turkish Pavillion (along with other 21 sponsors) for the period between 2014 and 2034, the Istanbul Tanpınar Literature Festival Sponsor in 2013, the International Sevgi Gönül Byzantine Research Symposium (initiated in 2010 and continuing), and the main sponsorship of Istanbul Biennial (together with Koç Holding) for the period between 2007 and 2016 (Vehbi Koç Foundation Culture, n.d.).

Sabancı Foundation‘s initiatives include Sakıp Sabancı Museum (2002), Mardin City Museum and Dilek Sabancı Art Gallery (2009), International Adana Theater Festival, National Youth Philarmonic Orchestra, Mehtap Ar Children's Theater, International Ankara Music Festival, Metropolis Archeological Excavations, Turkish Folk Dances Contest, supporting of State Museum of Painting and Sculpture in Ankara. Sabancı Foundation has total 16 cultural centers in Mardin, Adana, Istanbul, Antalya, Ankara, Edirne, Kocaeli, Malatya, Izmir and Kahramanmaraş (Sabancı Foundation Culture-Arts, n.d.).

Dr. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı Foundation has a “Modern Turkish Art Collection”, offers music scholarships since 1987, has been supporting Istanbul Foundation for Culture and Arts, Izmir Culture, Arts and Education Foundation, has been publicizing Eczacıbaşı Photography Artists Series since 2010 and has been giving Dr. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı Design Awards since 1988 (Dr. Nejat F. Eczacıbaşı Foundation, n.d.).

The group companies of Koç Holding (ex: Arçelik, Aygaz, Yapı Kredi Bank, Tüpraş), Sabancı Holding (ex: Akbank, Enerjisa, Çimsa, Teknosa), and Eczacıbaşı Holding (ex: Vitra) also participate in arts and culture sponsorship.

These expand the diffusion of the rationality behind the private support of arts and maintain the dominance of the respective three families, and their affiliated philanthropic foundations in the field.

For “ PART - 3 ” Click Here!

For “ PART - 1 ” Click Here!

MORE ON THE SUBJECT:

* AN EXISTENCE STORY: ISTANBUL IN TURKISH PAINTING - TURKISH PAINTING IN ISTANBUL by Elif Dastarlı (source)

*Legal framework constituted by “Law No: 5225”, “Law No: 5422”, “Circular in 2005” and “Regulation on Private Museums and Supervision”.

RELATED POSTS:

* Art vs. Censorship: Navigating the Boundaries of Expression

Will Attempts to Control Artistic Expression for Authority Succeed?

* The Enduring Love Affair: Exploring the Allure of Art

Why do we love the Arts? Will it cure us?

* The Artistic Alchemy: Unraveling the Correlation Between Persona, Psychology, and Art Styles

Is an artist's style determined by their persona? Can anyone become an artist, or is it an innate trait?